“I wasn’t seeing women represented in a way that made me want to be one.” – Callie Khouri

To be honest with you, I hadn’t heard of Callie Khouri before I stumbled across this quote. But reading it made me want to find out who she was. My search led me to Thelma and Louise, a movie written by Khouri and brought to life by director Ridley Scott. Reading about it made it pretty clear how powerful the movie and its message must have been when it came out in 1991, and how it rings true to this day.

It raised huge controversy as it was not only understood as being both feminist and anti-feminist, but also got criticized for being “male bashing.” With all these battling claims in mind, it is important to know that Thelma and Louise was one of the first movies to star two female characters in active leading roles.

Knowing how Khouri felt about the representation of women in film, I was super excited to see her characters in action. But, before I go deeper into the portrayal of Thelma and Louise, I’ll give you a short introduction to feminist film theory. Knowing the ideas behind feminist film theory will shed light on this controversial film.

Feminist Film Theory

Feminist film theory claims that the patriarchal system formats conventional movies and therefore inherits and supports its views and values. Since the camera represents a male point of view, movies are shot from a male perspective. As a result, there is a “male gaze” through which we see female characters.

This implies that women do not represent themselves, but rather that they represent an image that men project on/create for them. Therefore women are exposed to and staged for the “male gaze” at any given time and exist only as an object of sexual desire displayed for the male spectator.

What’s the scoop on Scopophilia?

Laura Mulvey, one of the first feminist film theorists to address gender issues in film, focuses on the pleasure in looking that the movie industry offers. In her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” she talks about the imbalance that exists between the male active bearer of the look and the passive female “to be looked-at-ness.” She picks up Sigmund Freud’s concept of scopophilia, which describes the pleasure in looking and divides it into narcissistic and voyeuristic scopophilia.

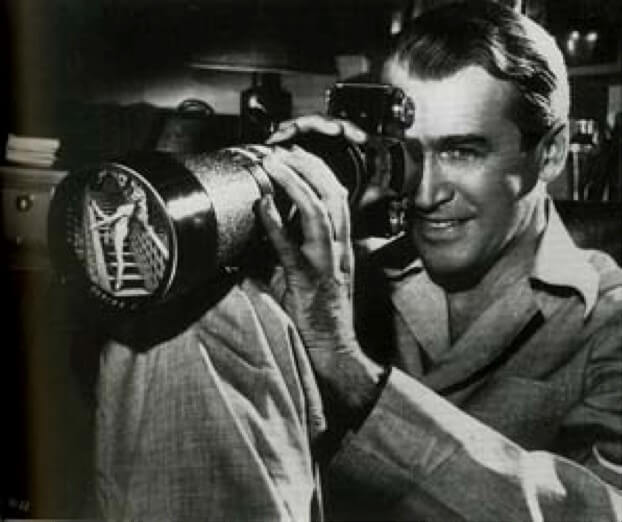

While narcissistic scopophilia describes the pleasure you feel by identifying with the protagonist on screen, voyeuristic scopophilia refers to the pleasure you feel by looking at an objectified being. Mulvey claims that the male spectator gets pleasure through both kinds of scopophilia while the woman is simply its object. By showing closeups and fragments of her body, she is not only sexualized but also fetishized.

The female character often acts as a motivator for the storyline to move forward or as exchange article between two men, but not as the active agent of the narrative itself. The woman is not just passive when it comes to the gaze, she is also the passive character when it comes to the plot.

The issue is that not only are women objectified, staged to please the male viewer’s desire, and generally lack narrative agency, but also that the female viewer and her desire is not addressed at all (an assertion that Mulvey got heavily criticized for). Even though there is much more to feminist film theory, that’s the general crux of it.

The “female gaze”

Getting back to Thelma and Louise, I want to point out two specific scenes that make it clear that the movie has a feminist touch.

Though there is no scene shot through the male gaze – meaning the camera never shows Thelma and Louise through an objectifying male point of view – the two women are still exposed to the gaze throughout the narrative. Men stare at them, turn their heads as they pass. etc.

If you haven’t seen the movie just a heads up this might spoil it a little for you:

- The rape scene: This scene shows the switch of the passive female and active male to a passive male and active female. As the scene opens, Thelma finds herself in the passive position of being acted upon by Harlan. Unable to defend herself, she fulfills the passive role of the motivator while the male character acts as the active protagonist that pushes the narrative forward. The camera acts as an objective observer. As soon as Louise appears, the camera jumps to a point of view shot, which makes it clear that the viewer is supposed to identify with the female lead. She turns the situation around and becomes the active character while Harlan ends up shot – passive as can be.

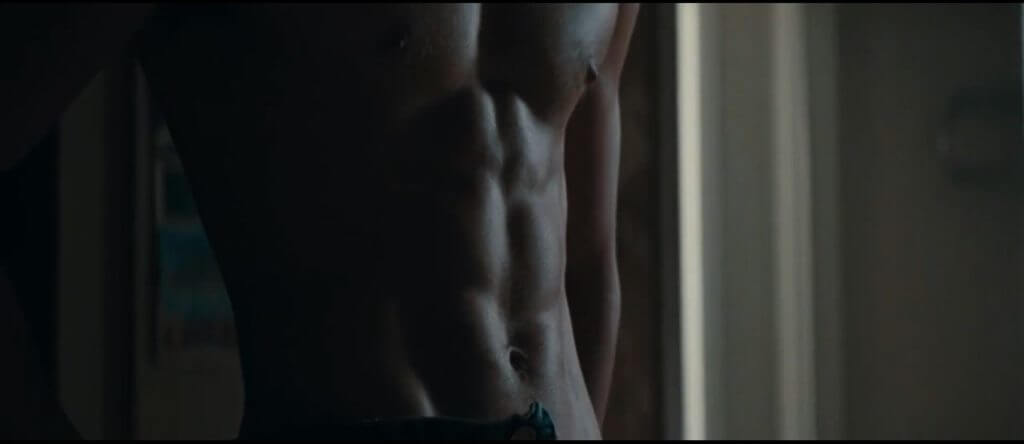

- The motel room: This scene goes without using the male gaze as well, but in addition to that it uses fragmentation and closeup shots to objectify Brad Pitt’s character. This scene plays with the to-be-looked-at-ness that women in film are exposed to and turns it around onto the male protagonist. It caters to the female spectator and fulfills her pleasure in looking. The male body is simply staged to please the viewer and to act as the motivation for the female leading role.

So next time you watch a movie, notice the way the camera guides you through the narrative. Be more aware of the “male gaze” and what it does to the characters. Switch your brain on and be critical of the way images are delivered to you.

As more people become aware of these issues, hopefully, more movies with interesting, strong and independent leading female characters will pop up to make women feel proud of the way they are represented.